About the Chuck Cooper Foundation

The Chuck Cooper Foundation was created to honor the legacy of Naismith Basketball Hall of Famer and NBA pioneer Chuck Cooper by building new pathways for others to follow. Founded by his son, Chuck Cooper III, the Foundation empowers under-resourced students through leadership development, mentorship, education, and career-focused programming that helps them blaze their own trails.

After losing his father at the age of 21, Cooper III made a personal promise to carry forward his legacy by creating meaningful opportunities for others. That commitment became the driving force behind the Foundation’s growth, from reclaiming a basketball court in East Hills to leading a respected nonprofit rooted in purpose and impact.

Since 2011, the Foundation has supported aspiring leaders through innovative programming and over $400,000 in educational awards. Today, it is expanding its efforts in workforce development and youth engagement through the Beacons of Light Outreach Program and a new internship initiative that reflects a strategic shift toward long-term impact. These programs are designed to help students develop the skills, confidence, and vision to lead, serve, and succeed.

We honor a trailblazer by helping others become one.

About Chuck Cooper

Chuck Cooper was a trailblazer in every sense. He broke barriers in basketball, business, and public service, opening doors for generations to come. His life was defined by courage, leadership, and impact. His legacy continues to shape minds, move institutions, and inspire those working to lead and break barriers of their own.

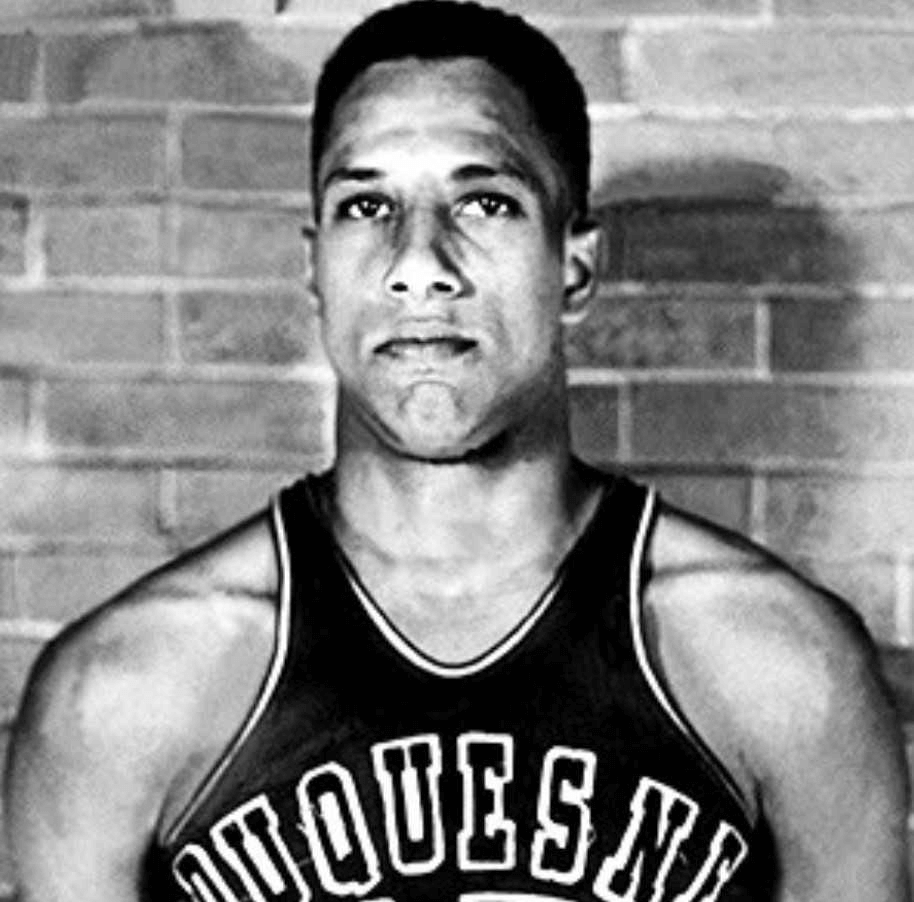

On The court

Chuck Cooper was more than just a pioneer; he was one of the top basketball players of his time. At Duquesne University, he became the second African American in NCAA history to earn consensus All-American honors, leading his team to three national championship runs. He was also named captain of the East-West College All-Star Game, becoming the first African American to hold that honor. Before entering the NBA, he signed with the world-famous Harlem Globetrotters, the top African American team in professional basketball during the era of segregation. In 1950, Boston Celtics owner Walter Brown made history by drafting Cooper, famously saying, “I don’t care if he’s striped, plaid, or polka dot.” Cooper earned NBA All-Rookie honors and helped lead the Celtics to their first winning season, laying the foundation for the 18-time world champion franchise and the winningest team in NBA history.

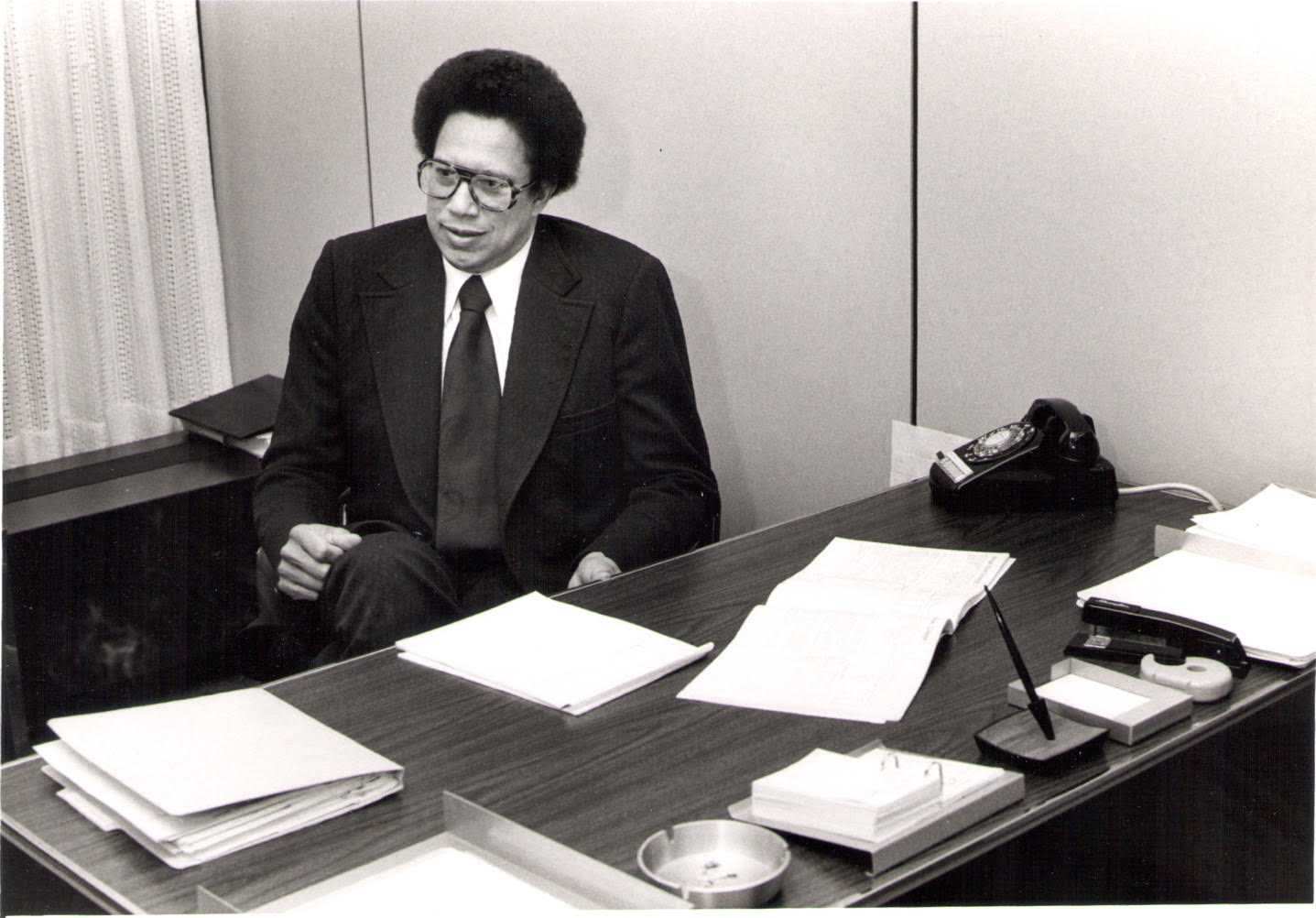

Off the court

After breaking barriers in professional basketball, Chuck Cooper continued to make history through public service, education, and corporate leadership. He earned a Master’s in Social Work from the University of Minnesota in 1960, then served on the Pittsburgh Public School Board. In 1970, he became the first African American department head in Pittsburgh's city government, serving as Director of Parks and Recreation. He transformed East Hills Park into one of the city’s finest public spaces. Later, as the first Black executive at Pittsburgh National Bank, he expanded access to banking and community development. His legacy lives on through two buildings named in his honor at Duquesne University: UPMC Cooper Fieldhouse, a $50 million renovation where the men’s basketball team plays, and the Chuck Cooper Building, once home to a PNC Bank branch and now housing university offices and public safety.

OUR BOARD MEMBERS

Charles H. Cooper III

Simone Quinerly

Joseph Dougherty

Cheryl Larkin

Robert Derda

Carolyn Cohen

Catherine Mills

Dick Roberts

Tom Rooney

Dr. Jimyse Brown

Sydney Harville

“What we are able to accomplish in our foundation would not be possible without the support and partnership of our corporate, university and community partners. I am so grateful to be able to honor my father’s legacy and to share his deep commitment and passion for education and community!”